That’s the title of a provocative post on a cheeky blog called Wait But Why. The entertaining article, by Andrew Finn, begins: “Soccer is the favorite sport for a measly 2% of Americans – despite the fact that soccer is by far the most popular sport globally.” Finn suggests it’s because the better team often loses, leading to spectator discontent. “Soccer is where sports justice goes to die,” he declares.

I beg to differ with Finn’s premise. The popularity of soccer in the U.S. is a lot higher than 2% of the population. Most of that, though, comes not from professional soccer but from amateur soccer–mainly youth soccer. I’d estimate that on any fall weekend upwards of 40 million people are playing or watching organized soccer–behind schools, in parks, at the odd multiple-soccer-field complex.

The failure of soccer on a professional level–it’s only truly popular in a few places like Seattle, Portland, Ore., and Kansas City–is an interesting business story, almost the flip side of the Michael Lewis book/Brad Pitt movie “Moneyball.” There has been some kind of pro soccer in this country since 1884, and a national championship almost every year since 1885 (far longer than the World Series, Lord Stanley’s Cup, the NBA finals and the Super Bowl). But most of the time, the leadership has been lackluster, including European expatriates not in tune with the local culture and baseball club owners without their hearts in it trying to fill their stadiums on off-days.

On the other hand, over the past half-century youth soccer has been on a roll. Why is this? My just-published debut novel, OFFSIDE: A Mystery, offers the unlikely answer, as follows:

While the professional game proved, ah, elusive, soccer became a widely played youth and amateur athletic endeavor in the US … Its dramatic expansion was due to the action of a single individual not associated with the sport, nor even with being terribly ethical or honest, or even a believer in fair play.

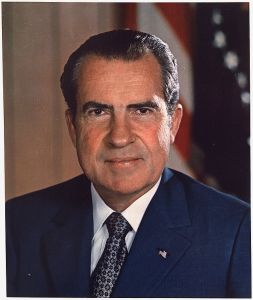

Richard M. Nixon.

On June 23, 1972, the Republican president of the United States signed what would become known as Title IX. The legislation prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex in any educational program receiving federal aid—like, say, just about every high school and college in the country.

As soon interpreted, Title IX forced thousands of schools to start more athletic teams for women. Soccer found itself the subject of a quick expansion. After all, it was easy to play, easy to coach, didn’t require expensive equipment and could be staged on already existing boys tackle football fields. Within three decades, US women’s teams were winning the big international titles that long had eluded the US men, including World Cups.

Being the student of history that I am–and recognizing that no youth soccer player today was alive in the 1970s–I couldn’t resist adding a postscript in the book.

[S]igning Title IX wasn’t the only momentous thing Nixon did that day in the White House. He also taped himself having a 90-minute meeting in the Oval Office with his Chief of Staff, H.R. Halderman. They discussed favorably how the Central Intelligence Agency could be used to obstruct and cover up the FBI’s investigation of the break-in by Republican political operatives just six days earlier at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex.

That didn’t work out too well for Nixon. Two summers later, the US Supreme Court unanimously ordered him to turn over to prosecutors a group of recordings including that one. It quickly became known as “the Smoking Gun Tape.” A mere three days after it became public, Nixon resigned in disgrace just ahead of certain impeachment and removal.

So throughout history, soccer was never far from the good and bad of society.

So as I see it, Americans love soccer. They just see no need to pay to watch the pros.